Genetic Algorithms are a stochastic search method inspired by the process of natural evolution, using techniques such as inheritance, mutation, selection, and crossover. In interviews, questions about genetic algorithms test a candidate’s understanding and application of this optimization technique to solve complex problems. It also examines their ability to implement solutions where traditional methods may fail. The uniqueness of genetic algorithms lies in their probabalistic transition rules and not deterministic ones, making them highly relevant for tasks involving machine learning and artificial intelligence.

Fundamental Concepts of Genetic Algorithms

- 1.

What is a genetic algorithm (GA) and how is it inspired by biological evolution?

Answer:A Genetic Algorithm (GA) is an evolutionary computational technique that draws on principles of natural selection and evolution. This method is particularly useful for solving complex optimization and search problems, but it’s also employed in various Machine Learning tasks, such as feature selection and neural network optimization.

Evolutionary Inspiration

GA’s design is inspired by how biological populations adapt to environments over time. It employs a process akin to natural selection, where fitter individuals (solutions to the problem at hand) are, probabilistically, more likely to survive and pass their beneficial traits on to the next generation.

Key biological concepts encapsulated by GA include:

- Genetic Variation

- Selection

- Inheritance

- Fittness Evaluation

This collective process is known as the genetic algorithm ‘cycle’.

Genetic Algorithm Cycle

The genetic algorithm iteratively proceeds through steps that parallel the biological mechanisms mentioned above. The core steps in a typical GA cycle are:

- Initialization: Initial set of solutions (often referred to as “individuals” or “chromosomes”) is generated.

- Evaluation: Each solution’s performance on the problem is assessed using a predefined objective function, often referred to as a fitness function.

- Selection: Solutions are probabilistically chosen based on their fitness to undergo reproduction, simulating natural selection.

- Crossover: For selected solutions, their genetic information (parameters in mathematical optimization problems or coding in discrete optimization problems) is exchanged to create new candidate solutions.

- Mutation: In some cases, genetic information of solutions is altered randomly to introduce diversity and prevent premature convergence.

- Replacement: The newly created solutions (offspring) are used to replace the less fit individuals in the current population, resulting in the creation of a new generation.

- Termination: The algorithm stops when a stopping criterion is met, such as a predefined number of iterations or an adequate solution is found.

Application of Genetic Algorithms

GA methods have been effectively employed in diverse fields including:

- Structural Design: For tasks like optimizing the wings of an aircraft for fuel efficiency.

- Mechanical Engineering: Where GAs can assist in the design of structures that can bear maximum load under given constraints.

- Finance: For problems that demand feature selection or portfolio optimization.

- Robotics: Such as in evolving gait mechanisms for legged robots.

- Data Science and Machine Learning: GAs can be used for hyperparameter tuning in supervised learning models or in feature selection tasks.

GA in Hyperparameter Tuning

GAs can be a pivotal piece of hyperparameter optimization. In this context, the individuals are configurations of hyperparameters for the learning algorithm, and the goal is to find a configuration that works best for a given dataset. These hyperparameters might include learning rate, batch size, and regularization strength in a neural network training process.

While training a learning algorithm, you’d evaluate each set of hyperparameters on a validation set and calculate its fitness. Then, at each generation, the genetic algorithm would generate new sets of hyperparameters, combining the best of the old ones and applying genetic operations like crossover and mutation, and continue its evolution until it converges, or you reach a predefined stopping criterion such as a maximum number of generations.

- 2.

Can you explain the terms ‘chromosome,’ ‘gene,’ and ‘allele’ in the context of GAs?

Answer:In genetic algorithms (GAs), like in natural genetics, the “chromosome,” “gene,” and “allele” analogies represent different levels of an individual’s feature representation decoding.

Chromosome

The chromosome is like the complete genetic makeup or DNA sequence of an individual. In GAs, it represents a full solution to a problem.

Depending on the problem being addressed, the chromosome may encompass different types or features known as genes.

Gene

A gene is a sequence of DNA that specifies the structure of a specific protein or features of an organism. In GAs, a gene corresponds to a distinct characteristic, such as the value of a parameter or a set of decisions specific to the task to be solved.

Considering a tangible example whereby the chromosome represents a potential airline schedule, a gene within that chromosome could specify the departure time for a particular flight.

This method allows solutions, represented by chromosomes, to be broken down into fundamental units, or genes, which can be examined in depth for improvements.

Allele

An allele is a variant form of a gene. It is one of the several possible nucleotide sequences the same gene can have, either between structurally similar chromosomes from different individuals or between paired chromosomes from a single individual.

In GAs, each gene will, therefore, have specific possible values, or alleles. For example, a gene representing departure time could have possible alleles such as specific hours and minutes, and flights.

The combination of alleles from different genes builds a specific chromosome, defining a complete solution.

Through crossover and mutation, these alleles are mixed and altered, reflecting the dynamic processes of natural genetics.

For instance, in the context of airline scheduling, the possible alleles for the departure time gene could range from “0800” to “2000,” potentially in increments of 100 minutes, and might be set as a particular schedule ahead of time.

During evolution, alleles from different genes within a single chromosome interact through reproduction methods like crossover and mutation, ensure diversity in chromosomes and prevent premature convergence.

- 3.

Describe the process of ‘selection’ in genetic algorithms.

Answer:Selection in genetic algorithms is the process of choosing which individuals, or potential solutions, from a population will contribute to the next generation.

Importance of Selection

Selection is a crucial step in the optimization process. It drives the algorithm to favor fit solutions and removes less desirable ones, mimicking the natural selection process.

Common Selection Operators

-

Roulette Wheel Selection: Also known as fitness proportionate selection, this method selects individuals with a probability proportional to their fitness scores. The fitter an individual, the more likely it is to be selected.

-

Tournament Selection: In this method, a small subset of the population (referred to as a “tournament group”) is chosen, and the fittest individual from that group is selected to move on to the next generation.

-

Rank Selection: Ranks individuals based on their fitness levels, with rank position determining selection probability. This method helps prevent premature convergence.

-

Stochastic Universal Sampling: This method selects individuals with uniform probability but ensures a broader representation of the population by allowing multiple selections based on fixed intervals.

Selection in Practice

The choice of selection method plays a pivotal role in the algorithm’s efficiency, convergence speed, diversity maintenance, and its potential for premature convergence.

The most suitable method depends on the problem at hand, the specific task, and the desired properties of the solutions. Practical applications often find a balance between exploration and exploitation, and selection methods are chosen to achieve this balance. For instance, some methods might prioritize the most fit individuals, leading to faster convergence, while others promote diversity to avoid premature convergence.

-

- 4.

Explain ‘crossover’ and ‘mutation’ operations in genetic algorithms.

Answer:Crossover and mutation are fundamental genetic algorithm operations that mimic genetic recombination and variation in natural systems.

Crossover: Gaining the Best of Both Worlds

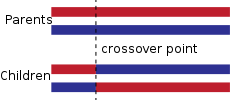

Crossover, also known as recombination or mating, is the genetic algorithm process of creating new candidate solutions (offspring) from existing ones. It simulates the way organisms exchange genetic material during sexual reproduction.

In algorithmic terms, it randomly selects a point in the binary string chromosome and “cuts” both parent strings at that point to create offspring. The new solutions are formed by combining (through crossover masks) parts of each parent solution.

Types of Crossover

-

Single-Point Crossover: The crossover point is chosen at random between two chromosomes, with all genes beyond that point in each chromosome swapped between the two.

-

Two-Point Crossover: Two crossover points are picked at random. Genes between the two points in the parent chromosomes are swapped.

-

Uniform Crossover: Each gene is selected from the parents with a 50% probability.

-

Multi-Point Crossover: Multiple crossover points are chosen and the segments between them are swapped.

Crossover in Discrete Domains

In problems where the solution space is discrete, strategies such as order crossover (for permutation problems), partially mapped crossover, and edge recombination operator (for TSP) are used.

Code Example: Single Point Crossover

Here is the Python code:

import random def single_point_crossover(parent1, parent2): crossover_point = random.randint(1, len(parent1) - 1) child1 = parent1[:crossover_point] + parent2[crossover_point:] child2 = parent2[:crossover_point] + parent1[crossover_point:] return child1, child2Mutation: Introducing Genetic Diversity

Mutation introduces randomness, or genetic diversity, in offspring by randomly flipping certain bits in the binary string.

This process ensures that not all offspring are mere duplicates of their parents and that the genetic pool retains a certain level of diversity.

The mutation rate, a key parameter in genetic algorithms, controls the likelihood of a gene being mutated.

Mutation in Discrete Domains

For problems with discrete solution spaces, mutation strategies are tailored. For example, in TSP, the 2-opt mutation can be employed.

Code Example: Bit Mutation

Here is the Python code:

def bit_mutation(individual, mutation_rate): mutated_individual = list(individual) for i in range(len(mutated_individual)): if random.random() < mutation_rate: mutated_individual[i] = '1' if mutated_individual[i] == '0' else '0' return ''.join(mutated_individual) -

- 5.

What is a ‘fitness function’ in the context of a genetic algorithm?

Answer:In a Genetic Algorithm (GA), a fitness function serves as the evaluation metric for candidate solutions. This function quantifies the “goodness” of each potential solution based on the problem’s objectives.

Purpose

-

Assessment: The function critically evaluates candidate solutions, assigning a numerical score based on their efficacy in solving the task.

-

Selection: Better-ranked solutions have a higher probability of selection for reproduction and survival, ensuring that beneficial traits propagate through the generations.

Key Considerations

-

Accuracy and Speed: The function should both accurately measure the solution’s fitness and do so efficiently.

-

Robustness: It should generalize well and not be overly sensitive to small changes in input values.

-

Normalization: Correctly scaling fitness scores benefits the selection process, ensuring that solutions are selected based on their relative, rather than absolute, fitness levels.

-

- 6.

How does a GA differ from other optimization techniques?

Answer:Genetic Algorithms (GAs) offer a unique approach to optimization by mimicking the principles of natural selection. Let’s explore how they contrast with traditional optimization methods.

Distinguishing Features

-

Operation Mechanism: GAs evaluate a population of candidate solutions iteratively, trailing a series of best-so-far solutions over numerous generations. In contrast, traditional optimization methods typically focus on a single solution throughout the process.

-

Emphasis on Exploration and Exploitation: GAs strive to maintain a balance between exploring the search space for new solutions while exploiting existing solutions for improvement. More classical optimization techniques like gradient descent generally focus on exploiting current information and may not explore as effectively.

-

Nature-inspired Elements: GAs draw inspiration from evolutionary traits like crossover (recombination), mutation, and selection (based on fitness levels). Conventional optimizers, in contrast, don’t necessarily model these biological concepts.

-

Search Strategy: Genetic Algorithms adopt a global search strategy that doesn’t overly rely on local information. Classical optimization methods, like hill-climbing algorithms, usually perform local searches around the best-known solution.

-

Parallelism in Exploration: In practice, a GA evaluates multiple candidate solutions simultaneously. This parallel search behavior contrasts with most traditional optimizers that consider one solution at a time.

-

Handling of Multi-modal and Noisy Functions: As GAs maintain a diverse population of solutions, they are often more reliable in locating multiple optimal points in multi-modal functions and are robust in noisy environments.

-

Exploration Depth: The adaptive nature of GAs can lead to a more profound exploration of the search space, providing the potential for unique and unconventional solutions. Traditional methods might get stuck in local optima.

-

Computational Demands: The inherent parallelism and global nature of the search in GAs might necessitate more resources (like CPU time or memory) compared to traditional optimizers, especially in certain applications.

-

Convergence Properties: While both GAs and traditional optimizers aim for convergence to an optimal solution, the convergence behavior of GAs is usually less predictable. This is due to the probabilistic nature of GAs, which introduce an element of randomness, making their convergence more probabilistic than deterministic.

-

Fitness Evaluations: GAs often require more function evaluations to achieve convergence, especially in high-dimensional or complex optimization problems, due to their population-based nature and the need for diversity management.

Code Example: Genetic Algorithm vs Classical Optimizer

Here is the Python code:

# Using GA from DEAP library from deap import base, creator, tools, algorithms import random # Define objective function def objective_function(individual): return sum(individual), # Set up GA creator.create("FitnessMax", base.Fitness, weights=(1.0,)) creator.create("Individual", list, fitness=creator.FitnessMax) toolbox = base.Toolbox() toolbox.register("attr_float", random.uniform, -1, 1) toolbox.register("individual", tools.initRepeat, creator.Individual, toolbox.attr_float, n=10) toolbox.register("population", tools.initRepeat, list, toolbox.individual) toolbox.register("evaluate", objective_function) toolbox.register("mate", tools.cxTwoPoint) toolbox.register("mutate", tools.mutGaussian, mu=0, sigma=0.2, indpb=0.2) toolbox.register("select", tools.selTournament, tournsize=3) # Run GA population = toolbox.population(n=50) algorithms.eaSimple(population, toolbox, cxpb=0.9, mutpb=0.1, ngen=100, verbose=False) # Using classical optimizer BFGS from scipy library from scipy.optimize import minimize result = minimize(objective_function, x0=[0] * 10, method='BFGS') print("Best solution using BFGS:", result.x) -

- 7.

What are the typical stopping conditions for a GA?

Answer:Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are optimized when there’s a mechanism to identify when to terminate the process. Several common stopping conditions help ensure that the algorithm does not run indefinitely while producing suboptimal solutions, considering both global fitness levels and computation resources.

Selecting a Beneficial Stopping Condition

The choice of stopping condition depends on factors like computational resources, scope of the problem, and characteristics of the fitness landscape.

-

For well-defined problems in small solution spaces, it’s feasible to find the global optimum. In such cases, stopping the GA once it converges can be enough.

-

When dealing with large solution spaces or multi-modal functions (with diverse local optima), the GA might benefit from running longer to explore more of the search space.

Common Stopping Conditions

- Fixed Number of Generations: The algorithm is evaluated for a predetermined number of generations.

Python code using

forloop:num_generations = 100 for generation in range(num_generations): # Run GA steps pass- Global Convergence: The algorithm stops when the best fitness value hasn’t improved significantly over several generations.

Python code with

ifstatement:no_improvement_threshold = 10 # Define the number of generations without improvement that will trigger the stop. best_fitness_values = [] for generation in range(num_generations): # Execute GA steps best_fitness = evaluate_best_solution() best_fitness_values.append(best_fitness) if len(best_fitness_values) > no_improvement_threshold and all(best_fitness_values[-1] <= val for val in best_fitness_values[-no_improvement_threshold:]): # stop the algorithm break- Resource Limits: Set the computation time or number of evaluations as stopping conditions.

Python code using

whileloop and time:import time max_runtime_seconds = 60 # Define the maximum run-time in seconds start_time = time.time() while time.time() - start_time < max_runtime_seconds: # Run GA steps pass- Solution Suitability: Terminate the algorithm when a certain level of fitness or solution quality is achieved.

Python code using

ifstatement and best_fitness:desired_fitness = 0.95 best_fitness = evaluate_best_solution() if best_fitness >= desired_fitness: # Stop the algorithm pass -

- 8.

How can genetic algorithms be applied to combinatorial optimization problems?

Answer:Genetic algorithms (GAs) found their niche in solving combinatorial optimization problems. Here’s a look at their core application areas.

Combinatorial Optimization

This branch of mathematics focuses on managing finite structures - multi-faceted with distinct solutions - to achieve an optimal configuration.

In real-life scenarios, individuals in a population can represent candidate solutions, each characterized by genetic information and performance attributes (fitness values).

Challenges and Solutions

Computational Complexity

Many combinatorial problems belong to the NP-hard complexity class, meaning that they often necessitate enormous computational resources to find an optimal solution within a reasonable timeframe.

Genetic algorithms provide a practical, if not “perfect,” opportunity by efficiently searching through extensive solution spaces.

Exploration-Exploitation Balance

An estimated solution can be upgraded through local search methods that are rigorous in their traversal of solutions. However, these techniques may cause the algorithm to get struck at a local maximum, disadvantaging the search for a global optimum.

Genetic algorithms maintain a balance between investigating new solutions (exploration) and operating on promising ones (exploitation). By doing so, they dodge the traps of local optima.

Code Example: TSP

Here is the Python code:

import numpy as np def total_distance(order, distances): total = 0 for i in range(len(order) - 1): total += distances[order[i], order[i+1]] total += distances[order[-1], order[0]] return total def crossover(parent1, parent2): size = len(parent1) a = np.random.randint(size/2) b = np.random.randint(size/2, size) mask = np.ones(size, dtype=bool) mask[a:b] = False offspring = [None]*size remaining = [i for i in parent2 if i not in parent1[a:b]] offspring[a:b] = parent1[a:b] j = 0 for i in range(size): if i < a or i >= b: while remaining[j] in parent1[a:b]: j += 1 offspring[i] = remaining[j] j += 1 return offspring def mutation(individual): mutate = np.random.random() < 0.1 if mutate: i, j = np.random.choice(len(individual), 2, replace=False) individual[i], individual[j] = individual[j], individual[i] def genetic_algorithm(distances, population_size=100, generations=1000): size = len(distances) population = [list(np.random.permutation(size)) for _ in range(population_size)] for generation in range(generations): scores = [total_distance(order, distances) for order in population] indexed_scores = sorted(enumerate(scores), key=lambda x: x[1]) population = [population[i] for i, _ in indexed_scores] for i in range(0, population_size, 2): parent1, parent2 = population[i], population[i + 1] offspring = crossover(parent1, parent2) for individual in [parent1, parent2, offspring]: mutation(individual) population[i], population[i + 1] = offspring, population[i + 1] return population[0], scores[0] # Example usage distances = np.array([ [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5], [1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4], [2, 1, 0, 1, 2, 3], [3, 2, 1, 0, 1, 2], [4, 3, 2, 1, 0, 1], [5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0] ]) order, score = genetic_algorithm(distances) print(order, score)The provided code solves the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) using a genetic algorithm, and serves as an example for combinatorial optimization.

Advanced Genetic Algorithm Concepts

- 9.

What is ‘elitism’ in GAs and why might it be used?

Answer:Elitism in Genetic Algorithms refers to the practice of preserving the best-performing individuals from one generation to the next, ensuring that valuable characteristics are not lost in subsequent iterations. This is achieved by simply carrying the best individuals, without any alteration, to the next generation.

Purpose of Elitism

-

Preservation of Superior Traits: Elitism safeguards the fittest individuals, preventing their dilution in the broader population.

-

Reduction of Exploration Risk: Sometimes, the GA might mistakenly discard a globally optimal solution in favor of exploring new possibilities. Elitism guards against this risk.

-

Effective Usage of Computational Resources: By focusing exploration on less promising solutions, computational resources are conserved.

Implementation

An elitism mechanism can be easily incorporated into GA’s evolutionary cycle, usually following the selection phase. It identifies the best individuals from the current generation and transfers them times to the next, where is determined by the specified elitism count or rate.

Code Example: Elitism

Here is the Python code:

def apply_elitism(population, next_gen, elitism_count): # Sort the population based on fitness sorted_population = sorted(population, key=lambda x: fitness(x), reverse=True) # Transfer the top individuals (elites) to the next generation next_gen.extend(sorted_population[:elitism_count]) # Example usage current_population = [ind1, ind2, ind3, ind4, ind5] next_generation = [] elitism_count = 2 apply_elitism(current_population, next_generation, elitism_count)In this example, the two fittest individuals from

current_populationare simply added tonext_generationwithout any alteration, as determined byelitism_count = 2.Note: The effectiveness of elitism in improving GA convergence and its computational costs has implications that vary from task to task.

-

- 10.

How do ‘penalty functions’ work in genetic algorithms?

Answer:Genetic Algorithms utilize various techniques to solve optimization problems, one of which is the use of Penalty Functions.

Role of Penalty Functions in Genetic Algorithms

Penalty functions contribute to genetic algorithm performance by:

-

Guiding Selections: They ensure that less fit individuals - those violating constraints - are less likely to be chosen for the next generation. This way, the genetic algorithm focuses on individuals that adhere to the solution space and the problem’s constraints.

-

Enhancing Global Exploration: By assigning higher penalties to individuals that violate constraints, the algorithm is encouraged to explore a broader solution space, focusing on those that incur lower penalties. This ‘explorative’ manner aids in finding global optima, especially in problems with non-convex solution spaces.

Penalty Functions in Genetic Algorithms

Genetic algorithms rely on penalty functions to address domains and problems with specific constraints.

Example: Positional Constraint in 2D Space

Consider the simple constraint of a point , such that . The following Python example demonstrates how a penalty function can be set up to account for this constraint:

Penalty Function:

def positional_penalty(x, y): return 1000 if x < 3 else 0Code Example

Here is a Python code snippet:

import random def positional_penalty(x, y): return 1000 if x < 3 else 0 def fitness(x, y): return 10 - (x - 3)**2 - (y - 3)**2 + positional_penalty(x, y) # Genetic Algorithm with Penalty population = [(random.uniform(0, 6), random.uniform(0, 6)) for _ in range(10)] best_individual = population[0] for generation in range(100): population.sort(key=lambda ind: fitness(*ind), reverse=True) best_individual = population[0] if fitness(*population[0]) > fitness(*best_individual) else best_individual # Perform crossover, mutation, and survival selection -

- 11.

Explain the concept of ‘genetic drift’ in GAs.

Answer:Genetic drift is a key concept in evolutionary biology that has a counterpart in genetic algorithms (GAs).

In the context of genetic algorithms, genetic drift refers to the random changes that can occur in a population over successive generations due to randomness in the selection and recombination processes. It’s a form of “unintended selection,” because the fittest individuals may not be guaranteed to be selected, leading to less fit individuals having the potential to dominate the population over time.

Mechanisms and Mathematical Basis

-

Selection Process: The genetic algorithm uses selection methods, such as roulette wheel selection or tournament selection, that introduce randomness. This randomness can sometimes lead to the selection of less fit individuals, especially in smaller populations.

-

Mathematical Basis: Genetic drift in GAs can be modeled using probability distributions. For example, in the case of roulette wheel selection, even less fit individuals have a non-zero chance of selection, contributing to genetic drift. This reduces the probability that the most fit individuals will be chosen, akin to the effects of genetic drift in natural populations.

Visual Analogy

Think of two jars, one labeled “Fit” and the other “Less Fit.” During each generation, a certain proportion of individuals from each group is chosen to populate the next generation.

-

In the absence of genetic drift, a perfect “shaker” mechanism would ensure that, over time, the “Fit” jar dominates and the “Less Fit” jar diminishes.

-

With genetic drift, the “shaker” motion is imperfect. Sometimes, more “Less Fit” individuals are chosen, leading to their over-representation in the next generation.

Code Example: Roulette Wheel Selection

Here is the Python code:

import random def roulette_wheel_selection(population, fitness_values): sum_fitness = sum(fitness_values) selection_point = random.uniform(0, sum_fitness) cumulative_fitness = 0 for i, individual in enumerate(population): cumulative_fitness += fitness_values[i] if cumulative_fitness > selection_point: return individualIn this example, the

roulette_wheel_selectionfunction implements a mechanism for randomly selecting an individual from the population based on their fitness values, introducing an element of randomness akin to genetic drift. -

- 12.

What is a ‘multi-objective genetic algorithm’?

Answer:A Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) is a specialized kind of genetic algorithm designed to handle multiple objectives or fitness criteria at once. This makes them well-suited for tasks that have competing goals and where solutions can’t be straightforwardly ranked as one being universally better than another.

Why Use MOGAs?

While a standard single-objective genetic algorithm can help find the best possible solution, a multi-objective approach is more diverse in its outcomes, also generating a set of non-dominated solutions referred to as the Pareto Front. This capability is especially valuable in real-world problems where several, possibly conflicting, goals must be optimized.

Representation

A key feature of MOGAs is that they operate on a population of solutions, and these solutions are generally evaluated with multiple objectives.

One way to visualize how MOGAs work is by using a two-dimensional space to represent the outcomes of two competing objectives, such as minimizing cost and maximizing quality. In such a space, the Pareto Front represents the set of solutions that are not dominated by any other solution.

Advances in Multi-Objective Optimization

With continuous improvements in algorithms and technological capabilities, combined with the potential to address a wider variety of objectives, the area of Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) has grown substantially.

Some modern techniques use metaheuristics like Ant Colony Optimization and Particle Swarm Optimization to explore the problem space, while others are based on mathematical principles like evolutionary strategies or Bayesian optimization. Integrating these approaches further enhances the capability and robustness of MOGAs.

- 13.

Can you describe what ‘gene expression programming’ is?

Answer:Gene Expression Programming (GEP), introduced by Cândida Ferreira in 2006, serves as a versatile tool for data analysis, predictive modeling, and algorithm optimization appropriate for both discrete and continuous problems.

Key Characteristics

- Chromosome Structure: Consists of one or more linear or circular chromosomes.

- Representation Scheme: Employs a simplified, thread-like encoding structure.

- Genetic Operations: Utilizes fundamental genetic operators (selection, crossover, mutation) but with proprietary strategies tailored to GEP.

- Fitness Calculation: Evaluates the performance and adaptability of individuals via optimized paradigms.

- Direct and Indirect Representations: GEP supports both direct (static) and indirect (dynamic) problem space mappings.

Foundations

GEP is a domain-independent optimizer fashioned on the pair of fundamental operations:

- Gene Expression: Represents the mapping from genotype to phenotype in the context of computer programs.

- Chromosome Evolution: Orchestrates the optimization journey involving genetic operators such as crossover and mutation.

Coding Mechanisms

-

Head and Tail Segments: The chromosomes in GEP are configured with a distinctive head (or initial segment) and tail (or subsequent part), each of which carries different functions.

-

Function Sets: Both fixed and dynamic functions can be incorporated, along with a set of terminal symbols.

-

Gene Mapping: Each gene, symbolizing a potential building block, is imbued with both a function and a feature.

-

Linker Genes: These establish inter-gene connections.

-

To enable genetic evolution in computer programs.

Encoding Schemes

GEP supports several modes of encoding, such as the traditional binary representation, the more versatile real number representation, and the “alf” (arithmetic) representation, which optimally addresses problems in continuous domains.

For matching optimized results, GEP permits a wealth of expression and encoding possibilities, effectively transforming encoding strings into executable programs.

Mechanisms for Genetic Operations

Crossover

GEP introduces a unique one-point crossover method, which pairs matching genes from candidate solutions based on a specified crossover point. This technique enhances diversity and robustness by preserving longer segments in each genetic constitution.

Mutation

GEP’s mutation approach operates at the level of individual genes. It safeguards computational schemes from drastic transformations and attains a balanced ratio of exploration and exploitation. Both terminal and non-terminal symbols can undergo mutation.

GEP Algorithm

Initialization

- Establish the initial chromosome configuration, mapping genes and linkers.

- Select the appropriate genetic functions and terminals.

- Set the fitness evaluation criteria.

Evolution Process

Condensing several evolutionary steps into a solitary generation:

-

Selection: Identify the most fitting genotypes for reproducing and propagating to the ensuing generation.

-

Crossover: Perform an exchange of genetic material at predetermined points along with each selected pair.

-

Mutation: Prompt modified genetics to cope with changes.

-

Result Evaluation: Once a new generation has been generated through genetic processes, the inherited and spontaneously transformed chromosomes are assessed for their investigative abilities in the problem space.

-

Termination Criterion: The algorithm concludes when a specific condition or a predefined number of iterations is met.

-

Output: The model with the highest computed fitness score is formulated for predictive and analytical tasks.

Applications

GEP is a dynamic computational tool with far-reaching adaptability, with applications spanning diverse domains. It is efficacious in:

- Data Analysis: For classification, clustering, and regression tasks.

- Feature Selection: Identifying the most influential features in a dataset.

- Function Approximation: Deriving a mathematical function to emulate a target dataset to enable predictive estimates.

- Model Optimization: Enhancing the performance and generalizability of machine learning models.

- Dataset Image Construction: Generating synthetic datasets to facilitate researching.

Recognized for its viability in genetic and evolutionary data analytics, GEP is a resolute tool in the armamentarium of machine learning and pattern recognition.

- 14.

What are ‘memetic algorithms’ and how do they differ from traditional GAs?

Answer:Memetic Algorithms blend genetic algorithms (GAs) with local search heuristics. By incorporating elements from local search methods and GAs, they can efficiently handle complex optimization problems.

Basic Components

- Population: A collection of candidate solutions.

- Selection: Identifies individuals for reproduction or survival based on their fitness.

- Crossover and Mutation: Methods for creating new individuals from existing ones.

- Local Search: Employs problem-specific techniques to improve the characteristics of individuals.

Memetic Algorithms: A Holistic Approach

Memetic Algorithms incorporate a multi-level, dynamic perspective to optimization problems. They refine solutions both across generations and within the scope of a single generation.

By applying problem-specific knowledge during local search, they can more effectively navigate the search space.

Architecture

Basic Genetic Algorithm

- Evaluate: Assesses the individuals’ fitness.

- Select: Picks suitable individuals for reproduction.

- Crossover and Mutation: Introduces diversity for the next generation.

- Replace: Updates the population with the new generation of individuals.

Memetic Algorithm

- Local Search Operator: Enhances solutions within a specific neighborhood.

- Adaptation Loop: Monitors factors like diversity and distribution, influencing subsequent operations.

- Imperialist Competition: A modification where a “leader” in a colony drives the search, mimicking the natural world.

Code Example: Memetic Algorithm

Here is the Python code:

import random # Initialize Population population = [random.randint(0, 31) for _ in range(10)] # Evaluate Fitness def fitness_function(x): return x**2 fitness_scores = {x: fitness_function(x) for x in population} # Local Search: Hill Climbing def hill_climb(iterations, point, step_size): for _ in range(iterations): new_point = point + random.randint(-step_size, step_size) if fitness_function(new_point) > fitness_function(point): point = new_point return point # Main Loop for _ in range(100): parent1, parent2 = select_parents(population, fitness_scores) child = recombine_and_mutate(parent1, parent2) child = hill_climb(10, child, 1) # Local Search if fitness_function(child) > fitness_scores[random.choice(population)]: replace_random(population, fitness_scores, child) - 15.

Define ‘hypermutation’ and its role in GAs.

Answer:Hypermutation is a genetic algorithm operator that introduces diversity to the population by increasing the mutation rate for a few generations.

It’s a useful strategy in fitness landscapes with narrow, steep valleys, ensuring that promising regions are not overlooked.

Mechanism

During hypermutation, the mutation rate is temporarily increased for a specified number of generations. After this period, it reverts to the standard mutation rate.

Code Example: Simple Hat Problem

Here is the Python code:

import random def hat_problem_fitness(phenotype): return sum(phenotype) def hat_problem_mutation(phenotype, mutation_rate): for i in range(len(phenotype)): if random.random() < mutation_rate: phenotype[i] = 1 - phenotype[i] return phenotype def hat_problem_hypermutation(phenotype, generation, hyper_mutation_rate, hyper_period): if generation % hyper_period < hyper_period / 4: return hat_problem_mutation(phenotype, hyper_mutation_rate) else: return hat_problem_mutation(phenotype, 1/10) def main(): population_size = 10 mutation_rate = 0.05 hyper_mutation_rate = 0.5 hyper_period = 5 current_generation = 0 while current_generation < 50: current_generation += 1 for individual in population: individual = hat_problem_hypermutation(individual, current_generation, hyper_mutation_rate, hyper_period) if __name__ == "__main__": main()